Restorative Approaches and Accessibility

Over the past few decades, restorative practice has gained traction across a variety of sectors, not just criminal justice. With increasing desire for organisations to be restorative and offer restorative services, comes an increase in the number of people accessing restorative tools. Traditionally these tools have been created for neurotypical individuals (individuals whose brain functioning is aligned with the prevailing idea of what is considered ‘normal’ functioning). However, with the improving societal awareness and understanding of neurodivergence (individuals whose neurocognitive functioning differs from this ‘norm’.), restorative practice must reflect this.

Through experience, WRAP realised there was a disproportionate number of neurodivergent individuals, from backgrounds such as criminal and youth justice, pupil referral units, social housing care homes and more, accessing restorative practice and yet there was, and still is, insufficient research (whether empirical or experiential/observational) around how to improve accessibility in the field.

More recently the governing body of restorative practice in the UK produced six principles to guide restorative work. Within this, accessibility was one of those principles.

Principles of restorative practice

The Restorative Justice Council principles of restorative practice is the overarching document setting out the core values that should be held by all practitioners in the field.

The six principles of restorative practice are:

- Restoration

- Voluntarism

- Neutrality

- Safety

- Accessibility

- Respect

WRAP acknowledges that there Is still a long way to go to address accessibility in restorative practice. Accessibility is a broad term relating to physical/cognitive/emotional access to this work. Practitioners should be doing as much as possible, being led by the individuals involved, to create an equitable outcome.

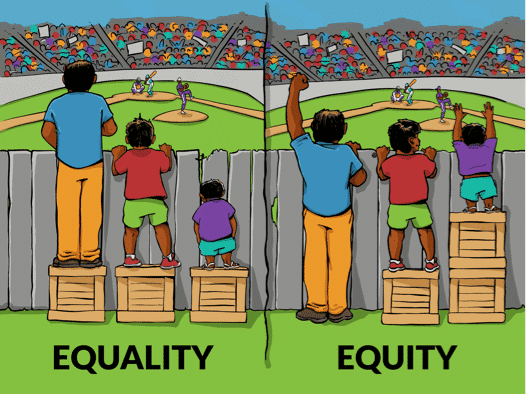

One element of equity that is traditionally misunderstood is that it is not the same as equality.

Equality is an important word to many people, but in fact can create an inaccessible service. A picture that has proven useful to explain the difference can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1. Equality vs equity

“Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire.”

In order for a service to be equal, service users are often treated the same. On the surface this looks good, but in fact limits the accessibility of the service. Some people require different needs to allow them access.

With this in mind, it is important to not just acknowledge that people sometimes need extra support but be willing to put it in place. Often, professionals are unsure of what can be done to make restorative work more accessible for neurodivergent individuals.

So, what have WRAP been working on?

In 2018 WRAP secured funding from the Waterloo Foundation to research and create new ways of making restorative practice more accessible. Over the past year, WRAP has been working with a variety of organisations from education to health to housing and is in the midst of developing new ideas. These ideas are continually tested in training and practice and will be shared with others in 2020.

What are some general tips?

- It is necessary to consciously and deliberately consider choice of words at all times. There can be no winging it, no mix up of words which we let pass, no ‘banter’ and we must model body language carefully.

- Being present in the room for the people we are working with is everything. No mobile phones, no smart watches, no conversation with a co-trainer or practitioner which is not a part of the training or practice in which everyone is involved

- If emotional outbursts happen, we need to understand them without making assumptions. We should be role modelling being restorative and we should be careful to remain regulated.

- Take time to build trust in each relationship. Restorative practice can be uncomfortable for some, but this can be overcome with a trusting, mutual relationship between those involved.

- One may need to be mindful of sensory issues around noises, lights, touch etc before planning exercises and choice of venue.

Some tips for circle practice

- Don’t force people into the circle. It can be an anxiety inducing experience for some. It is always voluntary.

- Split the circle into smaller circles to minimise anxiety of speaking in large groups

- Offer the choice of talking pieces – soft, tactile, light are usually preferable.

- Offer the option to pass if the person feels uncomfortable to answer when they receive the talking piece

- Give participants the question with plenty of time to think of the answer before being expected to answer. The question could be written down as well as verbally given. Keep it up as the talking piece goes around to remind people

Some tips for using restorative questions

One of the cornerstones of restorative practice are the restorative questions. There are many subtle variations out there, but generally they all follow a similar pattern of:

- A description of the event

- Emotions attached to that event

- Empathy building

- Problem solving and resolution discovery

For neurotypical individuals this can present difficulty. Societally, people are not encouraged to share emotions. Empathy can be seen as weakness and problem solving is someone else’s job. This combination means that answering the restorative questions can be very uncomfortable. In reality the questions may, in themselves, present as a barrier to working restoratively.

In particular, they may present a barrier if the person asking the questions only asks them verbally, expecting a verbal response. One’s emotional literacy, intelligence and vocabulary can play a fundamental part in their ability to answer.

In order to improve accessibility to the restorative questions, practitioners must be willing to use any medium available. Drawings, videos, puppets, dolls, kinetic sand, play-dough, blocks, rocks, shells, painting, drama, song, dance and anything else that can be thought of to support an individual to describe their answers.

For example, thoughts and feelings impact on actions is an abstract concept. To understand this requires higher level order thinking. Cognitively, this may be difficult for some and therefore simplifying to look at only feelings may be one adaptation.

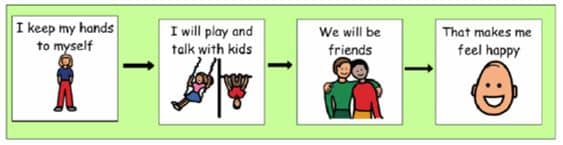

Giving example scenarios where participants can pick from a list of possible thoughts and feelings can be helpful. In essence, creating a simple picture exchange communication system.

When Bobby (insert picture of action) he might think (insert picture of a thought) and feel (insert picture for feelings)

Concluding thoughts

There is much room for growth in this area. As restorative practice becomes increasingly popular and widespread, more people come will inevitably come into contact with it. There is an immanent need to provide a more accessible service for all. If you are interested in finding out more, please get in touch with WRAP. We would be delighted to support you or to hear your own thoughts and ideas.